We spoke in a previous post about how choices around brand strategy or brand architecture on the heels of a merger or an acquisition send signals to key stakeholders. These decisions express to employees, investors, customers and the market where the entity is headed, what’s changing, what’s staying the same, etc. Making the right brand strategy decisions is critical to activate the full potential of the merger or acquisition.

The most fundamental brand architecture decision has to do with identity — the name, logo, and core message of the post-transaction company. In an M&A situation, there are 10 prevailing approaches — each with strengths and weaknesses.

While the right approach is situational, based on both the business strategy and nature of existing brand equities, it is important to understand the option set to frame the decision-making process and its content.

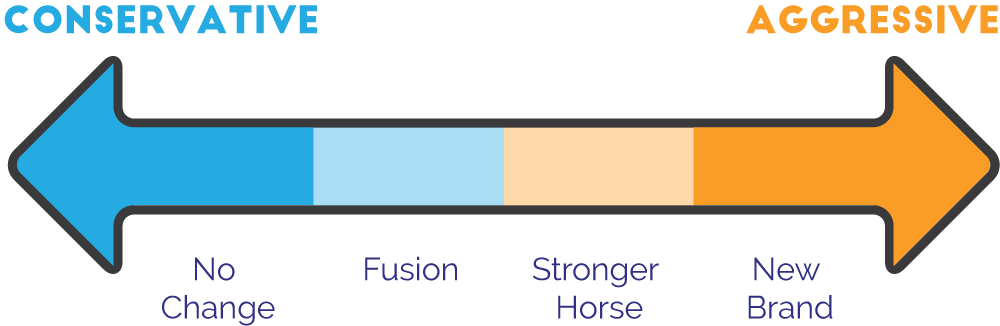

One way to assess these possible strategies is on a scale from ‘conservative’ to ‘aggressive.’ Let’s start on the conservative end of the spectrum.

No Change

The most conservative strategy is to make no change to the brand of either company. The acquiring company keeps its brand and so does the acquired company. This does not necessarily mean that the acquired brand operates independently, but that’s what the marketplace sees.

The No Change approach is generally best used in mature categories when the brands in question are clearly differentiated and either brand’s position would undercut the other if they were overtly linked. Quite often seen in the consumer packaged goods marketplace, No Change makes sense when stablemate brands are positioned against one another or designed to appeal to distinct segments in the same category.

One of the best examples of this strategy is Procter & Gamble. At the time of this post, the P&G portfolio boasts over 60 individual brands with dozens of products underneath each. The quintessential House of Brands, P&G has acquired and operates many differentiated brands. Following an acquisition, P&G preserves brand equity by keeping the incoming brand intact. This allows for increased aggregate market share by offering competing products in the same category.

The No Change approach can signal continuity to stakeholders and may help to make all team members — especially those who have worked to build the acquired brand — feel valued.

The ‘business as usual’ mentality that may come from the No Change strategy can, however, lead to a lack of perceptual or actual integration. There is no positive brand equity transfer from brand to brand and operational synergies may be unrealized. The rationale behind the merger or the acquisition likely included some degree of efficiency and gathering strength, which is obscured (at least in public) if the go-to-market brand does not progress.

Fusion

The second most conservative approach is Fusion. This strategy involves using brand identity assets from both partners in a merger or an acquisition and integrating them into the new corporate identity. There are four primary types of fusion strategies:

Straight Fusion is a combination of both entities’ names. A well-known example of this is ExxonMobil. In 1998, Exxon and Mobil agreed to a merger and the joint company became a mash-up of their two names: ExxonMobil.

Refreshed Fusion is an instance where the names are combined, but there’s a new graphic identity, symbol, icon, or topography that indicates that there’s newness here. An example is ConocoPhillips. The organizations merged in 2002, combined names and released a new visual identity. The logo and symbol were new to signify change but didn’t sacrifice the equity of either of the major merger partners.

Hybrid Fusion is a combination of the mix of names or visual elements. An example of this would be when United acquired Continental Airlines: the brand identity consisted of the United name, but used the Continental Airlines logo. It really was a mixture of brand assets and retained certain elements of both merger partners.

Endorsed Fusion is when the lead company endorses the acquisition in terms of brand architecture. An example of this would be when Gannett acquired CareerBuilder. CareerBuilder became careerbuilder.com, a Gannett company.

Fusion approaches are more geared to managing risk than activating potential. They prevent large-scale team and customer alienation, though sometimes create clunky and uninspiring brand scenarios. The mash-up of equities signifies a shared future, but risks alienating customers — especially if the entities were previously competitors.

Stronger Horse

The Stronger Horse strategy is when one brand is elevated over the other, based on whichever brand is consider to be stronger — based on size, reputational qualities, lack of brand baggage, brand potential or a wealth of other factors. While this strategy often elevates the brand of the company that initiated the acquisition or the larger or more dominant partner in a merger, there are four Stronger Horse variations of which to be aware.

Stronger Horse Forward is when the visual identity and the nomenclature of the larger or lead company in the deal is maintained, and the acquisition is absorbed and the other brand goes away. There are countless examples of the Stronger Horse Forward strategy as it is one of the most frequently used. One example is when DHL acquired Airborne Express. The Airborne Express brand ceased to exist and its assets were rolled up into DHL.

Reverse Stronger Horse is where the visual identity or the name of the acquired company, which often is much smaller (at least at a brand level), absorbs the lead company. An example of the Reverse Stronger Horse is when First Union acquired Wachovia. First Union had perceptual challenges and reputational damage. For this reason, and despite the fact that Wachovia was much smaller than First Union, the re-branding put the Wachovia name in the lead position. They considered the acquired brand, though much smaller, to be stronger — or at least in a position to define itself.

Phased Stronger Horse is a situation in which there is a temporary combination of brand identities and an integration strategy that ultimately ends up with a Stronger Horse brand situation where one name is ultimately elevated. This strategy leverages the benefits of Fusion early on while mediating the long-term risk of an awkward brand. One example is when Medtronic merged with Midas Rex. At first, they simply combined the names (Medtronic Midas Rex) for a time before dropping the Midas Rex name and becoming simply Medtronic. This approach makes sense for a variety of reasons, including buying time as long-term decisions are made and customers are educated on the company’s future.

Refreshed Stronger Horse is when the name of the lead company is adopted, but a new logo, a new symbol or a new color scheme is implemented to reflect the fact that there has been some change. One example of this is when Humana acquired United Health Group and kept the Humana name alongside a new visual identity.

While the benefits of the Stronger Horse approach include strong and clear communication of the brand direction and platform for internal efficiency, there is a clear risk of alienating certain stakeholder groups or losing customers in the transition.

Stronger Horse scenarios can create a winner/loser perception among team members and lead to a ‘conquering army mentality’ that hurts morale on one side of the aisle. There is also an increased risk of customer alienation. When one brand disappears completely, those who previously chose to work with the acquired entity may think about how to proceed.

New Brand

The most aggressive option following a merger or an acquisition is to develop an entirely new brand. This approach is usually most appropriate in categories undergoing an extreme level of transformation in which the merging entities wish to signal their own evolution. A good example is when GTE and Bell Atlantic, two old line phone companies, merged and created a new brand, Verizon.

This occurred at a moment when telecom was moving strongly into mobile — one can assume each legacy name would have faced perceptual challenges. This approach risked the equity of each brand — both of which were extremely prominent in their geographic trading areas — but placed a bet on a strong, shared and innovative future.

Conclusion

Creating a new brand is costly, time-consuming and very risky as it relates to protecting brand equity and customer relationships. The upside, however, is real — the ability to create something new to confront a changing world.

Activating the full potential of M&A requires the right brand architecture choices and effective implementation of this strategy — as such, it is critical for investors, executives and integration teams to understand these options and evaluate the forces that will best drive success.

This article originally appeared on the Finch Brands Blog. It has been republished here with permission.